by Margot Minardi

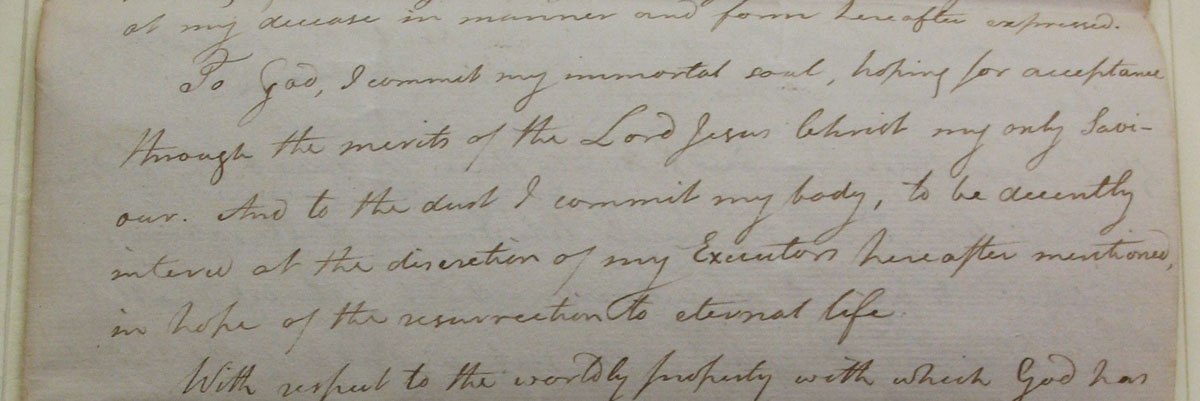

What might a historian of the future learn about you from a list of everything in your house? How might that historian come to know what’s important to you from how you plan to distribute your property after your death? In wills, the choices individuals made about how to dispose of their property help us to discern their personal values and priorities in life. Probate inventories—detailed lists of the property in a deceased person’s estate—enable us to imagine the physical spaces through which members of a household moved on a daily basis; from this material detail, we can make informed guesses about the conditions of their lives. The wills and probate inventories of Isaac Royall Sr. and his son are some of the most valuable sources we have for understanding the mindsets of these two elite men and interpreting what life was like for the enslaved and free residents of the Royall House.

Early American wills and probate inventories disproportionately represent men, white people, and the wealthy—unsurprisingly, as people in each of these categories were more likely to own property in the first place. However, property ownership was not restricted to people of extraordinary privilege, and consequently, the archives also contain probate records relating to women, people of color, and those of less-than-Royall wealth. An especially rich and revealing example comes from a formerly enslaved woman named Chloe Spear, who died in Boston in 1815. Like Belinda, the Royall House slave remembered for her moving petition for a pension from her master’s estate, Spear was reportedly captured in Africa as a child, eventually finding herself enslaved to a wealthy white man in the Boston area. But where Belinda’s life story—or a stylized version thereof—was recorded in her own lifetime in her petition, the details of Spear’s life are recounted in a short book called the Memoir of Mrs. Chloe Spear (1832). Authored by a white woman who was a fellow congregant at Boston’s Second Baptist Church, the Memoir appeared in print a full seventeen years after its subject died.

Why was Chloe Spear worth remembering, according to the author of the Memoir? The book stresses Spear’s piety and industry. Beaten by her master for trying to learn to read, Spear nonetheless acquired a psalter and not only learned to decipher the words but also embraced their spirit, becoming a lay leader of sorts within Boston’s Baptist community. After her emancipation, Spear toiled as a laundress and boardinghouse-keeper, earning enough money to purchase a house in Boston’s North End. Many of the Memoir’s details about Spear’s religious activities and her property acquisition can be corroborated by other contemporary sources, including her probate records (her will, inventory, and other documents associated with the will’s execution). But the probate records also provide a window into elements of Spear’s experience that the Memoir, authored as it was by a white woman, fail to illuminate.

The Memoir tells us little about Spear’s connections with other men and women of color. Here the will points toward a richer, more complicated story. Spear left five hundred dollars to her grandson, who lived in Salem. Six women—most of them identifiable as women of color who attended Second Baptist Church—received between twenty and fifty dollars each, in addition to Spear’s clothing and linens. Fifty dollars apiece went to Cesar Fletcher, whom Spear identified as “a man of Colour named for my late husband,” and Primus Grounds, “a Man of Colour and at Present a member of the Second Baptist Church in this town.” At one level, these bequests corroborate the Memoir’s claims that Spear was a deeply religious woman who worshipped at a church that admitted both black and white congregants. But the will also suggests that within that interracial church community, worshippers formed a tighter circle of mutual support and admiration, naming their children after one another and looking out for each other’s economic well-being. This was a social network that the white author of the Memoir might simply have been unable to see.

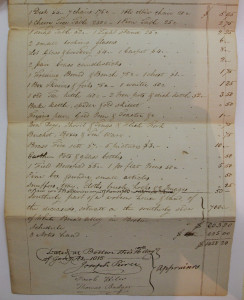

Spear’s probate inventory, meanwhile, builds a picture of her economic life that confirms the Memoir’s account of her worldly success, even while fleshing it out with material detail. While the Memoir singles Spear out (very few people, rich or poor, black or white, male or female, had book-length biographies written about them by their friends), the probate records allow us to look at Spear in the context of the large pool of people whose wills were executed around the same time. A sample of fifty wills from the year of Spear’s death shows that the total value of her estate fell about in the middle. Given that she had been a slave some thirty years earlier, and that the population of will-writers skewed wealthier than the general population, this is evidence of Spear’s impressive economic advancement over the course of her life as a free woman. Moreover, the items listed in her probate inventory allow us to imagine what her day-to-day life might have been like. Her property included: utilitarian household items (such as a “Bake Kettle Spider & old Skillett”); the tools of a laundress (“1 Pair Flat Irons,” “1 Folding Board & Bench”); and several luxury goods and furnishings (“1 Ebony Tea Table,” “2 Small Looking Glasses,” “5 Pictures,” and a seven-dollar “Brass Fire Sett”). Although Spear clearly scrimped and saved (her assets included $625 in “Notes of Hand,” or IOUs), she also allowed herself some of the household goods that served as markers of refinement in the early nineteenth century.

At first glance, it might seem that probate records are primarily about money and how it gets distributed after someone’s death. But probate records also give us insight into meaning in a person’s life. Chloe Spear did not leave us an account of her life in her own hand; indeed, she signed her will with a simple X. But she tells us something of who she was through her disposition of her hard-earned wealth.

Margot Minardi is an Assistant Professor of History and Humanities at Reed College in Oregon, where she teaches courses in colonial and Revolutionary American history, early African American history, and social reform. She is the author of Making Slavery History: Abolitionism and the Politics of Memory in Massachusetts, published in 2010, and is a member of the Royall House and Slave Quarters’ Academic Advisory Council.