Of all the residents on the Royall estate in the 18th century, free or enslaved, perhaps the best-known today is Belinda Sutton, an African-born woman who was enslaved by the Royalls. We know much more about her than we do about most of those who experienced slavery, but it is still frustratingly little. Most of what we know about her life comes from a remarkable 1783 petition to the Massachusetts General Court, in which she recounted her life story and claimed a pension from the estate of Isaac Royall Jr. Her public assertion of her rights has given her a place in history and public memory.

Although the 1783 petition had long been known to scholars, it was only in 2015 that the launch of a comprehensive database of Massachusetts antislavery petitions brought to light additional petitions that allow us to track her persistent efforts to ensure that she received the pension confirmed by the legislature. A history of missed payments meant that Belinda would renew her claim five times over the course of a decade.

The petitions that came to light in 2015 also informed us for the first time of her marriage. In her 1783 petition and earlier records, Belinda Sutton had been identified simply as “Belinda.” But in a 1788 petition, she described herself as “Belinda Sutton of Boston in the County of Suffolk Widow.” We do not know who her husband was, or when they married. She signed as Belinda Sutton again in a 1793 petition.

Two documents from 1785—one a petition, the other a receipt—identify her as “Belinda Royal,” in accordance with the common practice of assigning a slaveholder’s surname to formerly enslaved individuals. Since her first petition was made public in 1783, she has been commonly referred to as “Belinda Royall.” Until the subsequent petitions came to light in 2015, however, our museum chose to call this strong African woman “Belinda,” the name she called herself in the petitions of which we were aware. With new knowledge of her married name, we now refer to “Belinda Sutton,” as we believe this is the closest she came to having a name of her own choosing.

The first known documentation of Belinda appears in the Medford, Massachusetts, church records for 1768, when her son Joseph and daughter Prine were baptised.

The next mention is in Isaac Royall Jr.’s will, dated May 26, 1778, and written during his exile to England. He notes in a codicil: “I do also give unto my said daughter [Mary Royall Erving] my negro Woman Belinda in case she does not choose her freedom; if she does choose her freedom to have it, provided that she get Security that she shall not be a charge to the town of Medford.”

Royall instructed his friend Willis Hall, Medford’s town clerk who served as the executor of his will, to pay Belinda “for 3 years, £30,” and presumably this payment was made when Royall died in 1781.

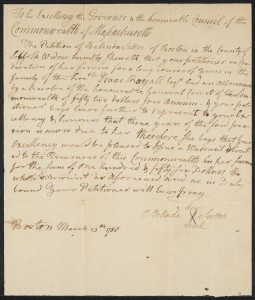

In February 1783, Belinda presented a petition to the Massachusetts General Court, the new state’s legislative body, requesting a pension for herself and her infirm daughter—assumed to be Prine—from the proceeds of Isaac Royall’s estate. Willis Hall was first witness to the petition and his son was second. Belinda signed the petition—and all the subsequent legal documents we have from her—with an X, indicating that she was unable to write or, probably, to read. Scholars speculate that Prince Hall, an acknowledged leader of Boston’s black community at the time, is likely to have written the petition.

The Massachusetts legislature approved an annual pension of fifteen pounds and twelve shillings, to be paid from Royall’s estate, but just one payment was made, and in 1785, she petitioned the legislature for payment of the amount previously authorized. (We also know that she received two pounds two shillings from the stepson of Mary Royall Erving in December of that year; we have no way of knowing whether this reflects a gift or payment for work performed.) Belinda again petitioned the Massachusetts legislature in 1787 and was again granted one year’s allowance.

Belinda petitioned for three years’ back pension in 1788, now identifying herself as widow Belinda Sutton. In 1790 Willis Hall refused to make another payment “without a further interposition” from the legislature, which appointed a committee to investigate and ordered resumption of the payments, but Belinda’s 1793 petition—signed again as Belinda Sutton—shows that this did not occur.

The 1793 petition is the last documentation of her life we currently possess. In 1799 Willis Hall requested the balance of the estate from the state treasury for distribution to Royall’s heirs, stating that the last of “two family servants who were left behind” was now dead.

Belinda Sutton’s eloquent petition of 1783 is among the earliest narratives by an African American woman. It has inspired poets and fascinated historians. It has been seen by some commentators as the first call for reparations for American slavery. And it opens a rare window onto the life on an enslaved woman in colonial North America.

To read the full text of Belinda Sutton’s first petition, click here. All of her petitions are available through the Antislavery Petitions Massachusetts Dataverse, maintained by Harvard University.

“Belinda’s Petition,” a Poem by U.S. Poet Laureate Rita Dove

Belinda Sutton’s eloquent petition was the inspiration for this poem by Rita Dove, U.S. Poet laureate from 1993 to 1995. Ms. Dove has published multiple books of poetry, essays, and fiction. Recipient of numerous literary fellowships and awards, including a Pulitzer Prize for her poetry collection Thomas and Beulah, she is currently a Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Virginia.

To read Rita Dove’s poem Belinda’s Petition, click here.

Why Was Belinda’s Petition Approved? by Margot Minardi

Belinda Sutton’s petition for a pension from Isaac Royall’s estate is often cited today as an early argument in favor of reparations for slavery. What are we to make, then, of the legislature’s favorable response? Historian Margot Minardi argues that in the context of its own time, the pension granted to Belinda did not necessarily challenge the legitimacy of bondage.

Click here to read the article.