Africans and African Americans enslaved in 18th-century Massachusetts yearned for freedom. As the formerly enslaved poet Phillis Wheatley put it in a letter of 1773, “In every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance.”

The political debates leading up to the American Revolution gave new salience to the issues raised by black bondage. Some Patriots believed that slavery was immoral, and that it was inconsistent to allege that natural or inalienable rights belonged only to white colonists. In 1764, for example, James Otis argued that the colonists were by the law of nature free born and extended his argument to all men, white or black. Ten years later, Abigail Adams wrote that it was “iniquitous” for whites to fight for their own freedom while denying it to others who had just as good a right to it.

Enslaved and free blacks in Massachusetts proceeded to deploy such Revolutionary arguments and rhetoric to argue for freedom. Over the course of the 1770s they submitted to the colonial governor and legislature and, later, state legislature, numerous petitions calling for the end of slavery, in which they argued that they had “in common with all other Men, a natural and unalienable right” to freedom.

Those petitions were not granted, but the new state constitution adopted in 1780 opened the door to a series of legal cases that led to the end of slavery in Massachusetts. Article I of the constitution’s Declaration of Rights argued that all men were “born free and equal.” Although the phrase does not appear to be have been inserted in the interest of abolition, lawyers and others opposed to slavery quickly seized upon it.

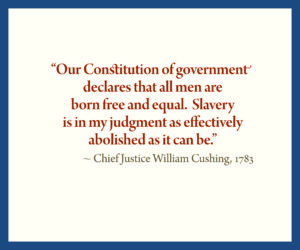

As early as 1781, a local court of common pleas found in favor of Elizabeth (Mum Bett) Freeman and a man named Brom when they argued that they were being held in slavery unlawfully. And in 1783, in a freedom suit brought by Quock Walker, Chief Justice William Cushing of the Supreme Judicial Court in effect told the jury that slavery had been abolished by the new state Constitution. Elizabeth Freeman was later remembered as saying, “Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it—just to stand one minute on god’s airth a free woman—I would.”

The federal census of 1790 recorded no enslaved people in Massachusetts, although wills and probate inventories reveal that a small number of individuals continued to be held in virtual slavery in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. And life continued to be difficult for the newly freed, as racial prejudice and discrimination limited both economic opportunity and participation in civic life.

We know little about the end of slavery on the Royall estate itself. At least ten of those enslaved by the Royalls apparently continued to live and work on the property after Isaac Royall Jr.’s departure in 1775. One of these was Belinda Sutton, whose petitions to the Massachusetts legislature seeking a pension from the proceeds of Royall’s estate open a window on both the experience of slavery and the difficult circumstances freedpeople faced in post-Revolutionary Massachusetts.