Although Isaac Royall Jr. was a prominent member of Massachusetts’ pre-Revolutionary elite, he left relatively little mark on public affairs in the colony. Perhaps his most enduring public legacy was the bequest in his will to Harvard College. On his death in 1781, the College was entitled to receive from his estate between 900 and 1000 acres of land in Massachusetts, to be used to endow a professorship in either law or medicine. The lands were sold in a series of transactions between 1796 and 1809, and the proceeds were eventually used in 1815 to establish Harvard’s first professorship in law.

The Royall Professorship was not only the oldest but “arguably the most distinguished chair in American legal education.” Its last incumbent, Janet Halley, took the occasion of her inaugural lecture in 2006 to reflect on the legacies of the Royall bequest for the Law School community—not only Royall’s gift and a series of eminent predecessors, but also an enduring connection to the enslaved individuals whose labor had made his family’s great wealth possible. In 2022, as part of the process of confronting Harvard Law School’s history, the Royall Professorship was retired.

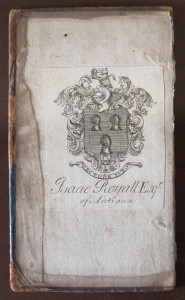

Royall’s bequest was visibly commemorated for many decades in the Harvard Law School’s seal. In 1937, the Harvard Corporation authorized the Law School to adopt for its seal a design, developed for the university’s tercentenary the preceding year, based on the Royall family crest. The seal, modeled after Isaac Royall Sr.’s bookplate, featured three sheaves of wheat—a traditional heraldic symbol of agricultural fertility and abundance.

It is not known when the Royall family first used this device, which was also stamped on wine bottles whose remains were discovered during archaeological digs at the Royall House and Slave Quarters. Isaac Royall Jr.’s iron seal, which he would have used to emboss the coat of arms on documents and correspondence, verifying their authenticity, is owned by Harvard Law School; its 2001 rediscovery in the university’s Widener Library is the subject of an article in the Summer 2001 issue of the Harvard Law Bulletin.

In November 2015, following student protests over the use of the Royall crest as the Harvard Law School’s symbol, the School’s Dean appointed a committee of 12 faculty, students, administrators, and alumni to review the history of the shield and make a recommendation on whether it should continue to be used or replaced. The Committee issued its report in early March 2016, recommending that the shield be removed. The recommendation was not unanimous: Professor Annette Gordon-Reed offered “A Different View,” joined by student Annie Rittgers, recommending that the shield continue in use, tied to a historically sound interpretive narrative.

The Dean of the Law School endorsed the Committee’s recommendation and asked the Harvard Corporation for authorization to retire the shield. On behalf of the Corporation, the President and the Senior Fellow approved the recommendation to retire the shield in a letter to the Dean on March 14, 2016.

A report issued in April 2022 by the Presidential Committee on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery recounts in detail the many ways Harvard University participated in, and profited from, slavery, and the long history of discrimination against, and exclusion of, Black people by the university. In a statement to the Harvard Law School community shortly after the release of the committee’s report, Dean John F. Manning announced several initiatives to honor and commemorate the enslaved people whose labor generated wealth that contributed to Harvard Law School’s founding.

Among these was the retirement of the Royall Professorship. Manning noted that through her scholarship and teaching, Janet Halley had “heightened awareness of the Royall family’s involvement in the history of enslavement in Colonial Massachusetts.” The dean announced that Halley had resigned from the Royall Chair, which will never be occupied again.