Anyone who has visited our museum, explored our website, read our Facebook posts, or followed our Twitter feed knows that the Royall House and Slave Quarters does not defend the actions of Isaac Royall, father or son. We are not apologists for the Royalls, and we feel no need to protect the family’s legacy. Our goal is to tell their story accurately, in the context of Europe and America’s legacy of chattel slavery, and in particular of the North’s direct colonial-era involvement and continued complicity in slavery.

There has been considerable interest in the Royalls’ role in the suppression of a planned slave revolt on Antigua in 1736. Much of the media coverage of a Harvard Law School committee’s 2016 recommendation to remove the Royall family crest from the school’s official seal included some variation on the claim that the Royalls were known to have burnt 77 enslaved people to death on the island. Agreeing with the committee that “it is important to correct certain misconceptions,” we offer here a description of what scholars believe actually happened.

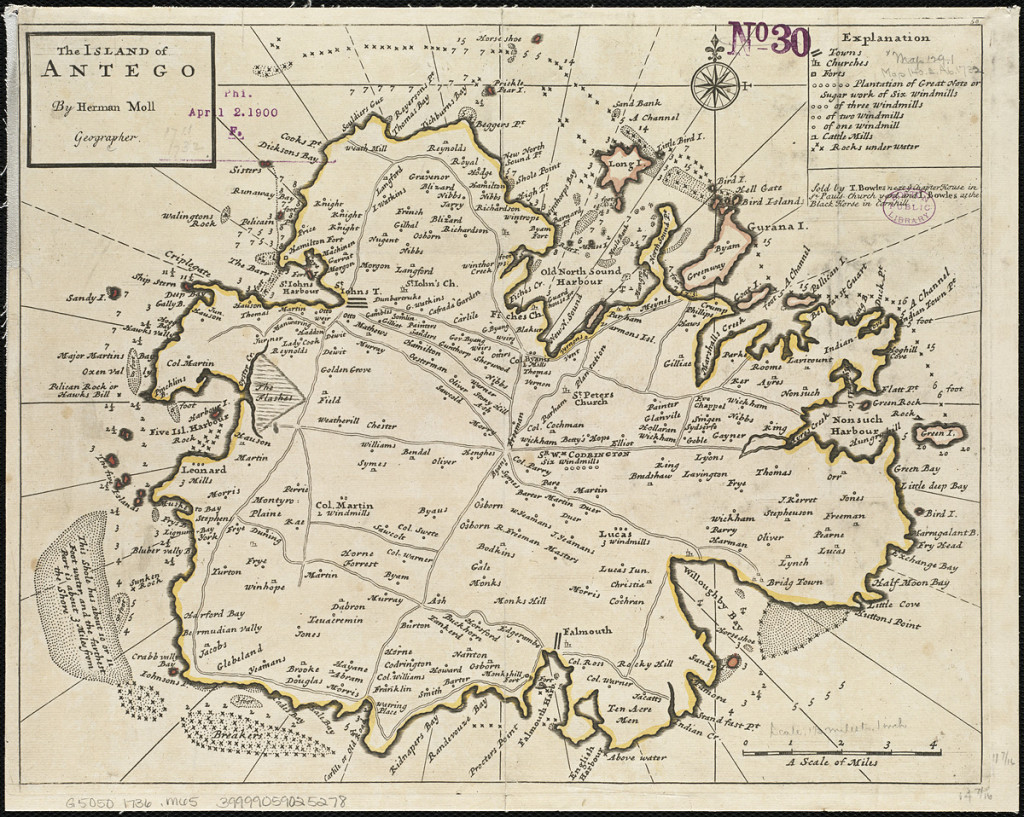

Island of Antego, Herman Moll, 1736. Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library. To zoom in, visit the Boston Public Library’s webpage.

Historians continue to debate whether there really was a plot by enslaved Africans to kill Antigua’s 3,800 white inhabitants and take over the island. But there is no doubting the reality of the terrible punishments meted out to those believed to have taken part in the conspiracy. A total of 132 enslaved persons were convicted, and 88 executed: five were broken on the wheel, six were gibbeted, and 77 were burned at the stake.

The executed individuals were held in bondage by a total of 60 different individuals and estates. Only one of them, Hector, was enslaved by the Royalls. Identified as a driver, or overseer, he was among those burned at the stake. Isaac Royall Sr. received £70 in compensation for his loss.

Quaco, another man enslaved by Royall, was “reprieved at the Stake, upon his Promise to make Discoveries of great Moment,” according to the island’s governor. “Till I know how well he has made good those Promises, I cannot Say how he is to be disposed of.” Quaco’s “discoveries” were apparently sufficient that his life was spared and he was banished to the island of Hispaniola.

As the Harvard Law School committee put it, “there is no evidence of the role—whether prominent or otherwise—that either Isaac Royall played in suppressing the revolt, nor is there any evidence that would let us determine whether either one was any more or less brutal than his fellow slave-owners on Antigua, although historians have long recognized that conditions of slavery in the Caribbean were markedly harsher than they were in the mainland colonies.”

Responsibility for these brutal executions lies with the colonial government of Antigua and the island’s slaveholding elite as a whole. That said, there is no reason to believe that the Royalls did not support the punishments inflicted on the presumed conspirators.

The quotations about Quaco are taken from David Barry Gaspar, Bondmen and Rebels: A Study of Master-Slave Relations in Antigua (Baltimore, 1985); other quotations are from the Harvard Law School committee, whose full report is available here. More information on the connection between the Royall family and Harvard Law School is available here on our website. Mike Dash provides an introduction to the events on Antigua in 1736 here in “Antigua’s Disputed Slave Conspiracy of 1736” in Smithsonian.com, January 2, 2013.