A central feature of our site is the only known extant separate slave quarters in the northern United States. Extensively renovated soon after the site first opened as a museum in 1908, the space is now used for programs and exhibits. Our long-term goal is to restore the building for the interpretation of its original purpose.

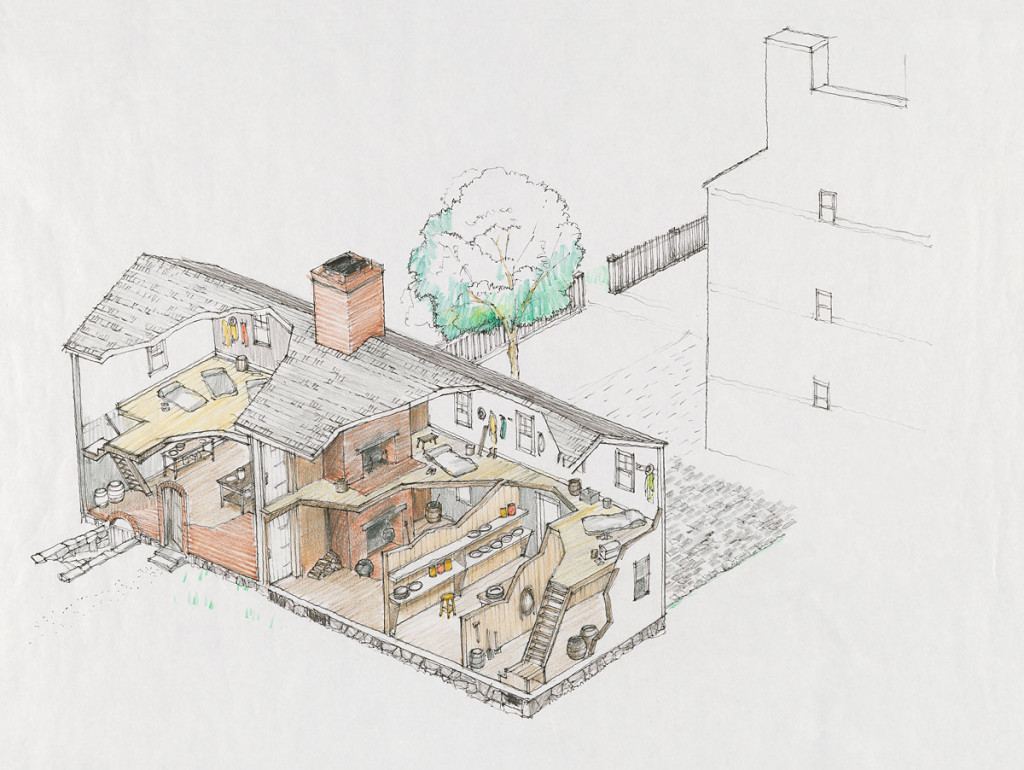

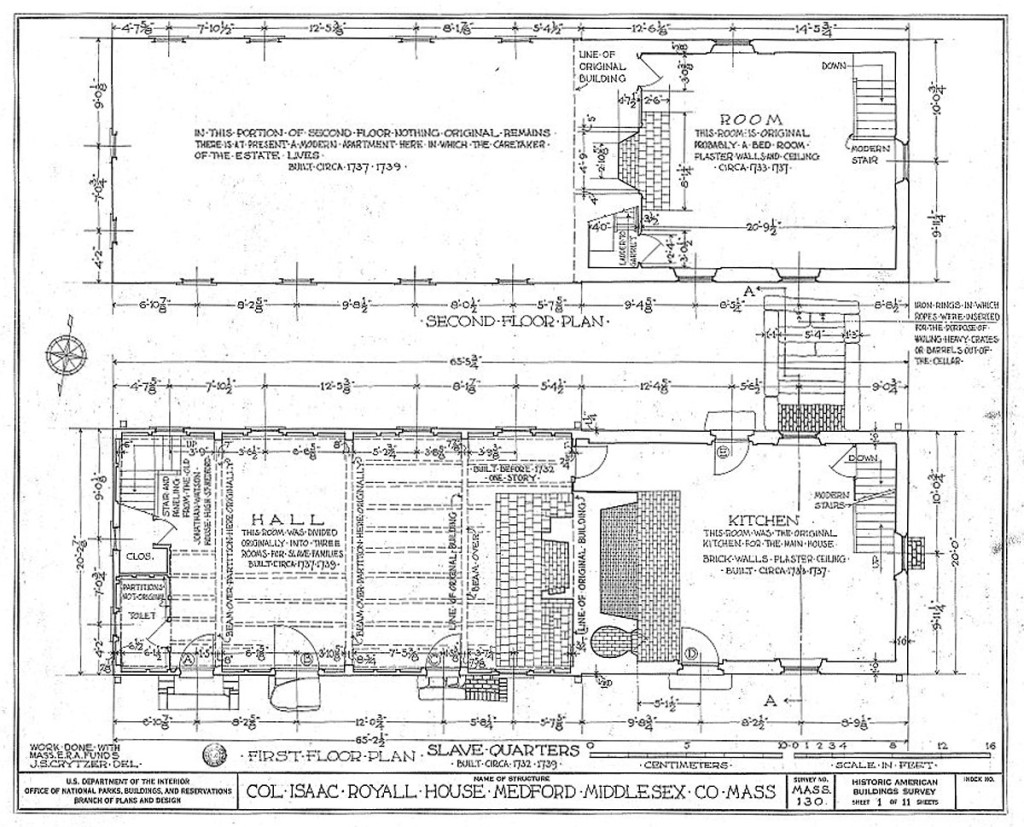

When Isaac Royall Sr. expanded a colonial farmhouse into a three-story Georgian mansion in the 1730s, he also borrowed from practices common in the Caribbean and constructed a summer “out kitchen” to keep heat away from the house in warmer temperatures. We know from archaeological evidence that around 1760, a simple clapboard addition more than doubled the size of this brick “out kitchen,” creating what is known today as the Slave Quarters. The first floor of the addition—located just thirty-five feet from the mansion—was originally divided into three narrow rooms, each with a door opening onto what was then a cobblestoned courtyard.

Unfortunately, there is little documentary evidence on the history of this building and its use. In 1997, preservation expert Anne Grady gave a talk on our site, sharing her research into the building’s evolution. We include below an excerpt of that 1997 talk reviewing the documentary evidence for the history and use of the structure. Since this talk was delivered, archaeological evidence has confirmed Grady’s insight that both portions of the structure are from the 18th century, with the addition dated now to about 1760.

An Excerpt Regarding Building Evolution: from Anne Grady’s talk on the Slave Quarters, 1997

“Now, I’d like to talk a little bit about the documentary evidence with regard to the buildings on the property. In Isaac Royall’s inventory of 1739, the one I have mentioned already several times, listed along with the contents of the house are the dwelling house, the out kitchen (this building here), pigeon house, corn house, coach house and stable, two old barns, one new barn, two old ditto (barns).

Detail from the probate inventory taken upon Isaac Royall Sr.’s death in 1739

In the inventory that was taken of Isaac Royall Jr.’s estate which was in 1778, and this is a small detail of the Pelham map of the Boston area from 1777 in which Mr. Pelham, for the benefit of the English laid out all of the roads and fortresses and so on to help with the American Revolutionary struggle. But you see, the dark rectangle in the front, I assume must be the house. I truly believe that the building to the left of that is the slave quarters in their current configuration on the outside, at least, and then the others are the various buildings associated with the farming operation.

Detail from “A plan of Boston in New England with its environs” by Henry Pelham, 1777

Isaac Royall’s inventory says only that mansion house and all the buildings adjacent with gardens and yards are worth 6000 pounds. The farm belonging to the mansion house is worth 10,000 pounds. The inventory is just a fascinating document. It makes no references to “Negroes” since they have been disposed of elsewhere, and it does not list contents room by room. It goes on for many pages and details the incredible wealth of the man and the estate value at that time was 50,700 pounds.

But there is another description of the estate that was submitted by the husband of his daughter in 1782 when he was trying to get his wife’s inheritance restored. And I think if you look at this plan you may be able to imagine buildings that are references in the description of the estate. “Situated 5 miles from Boston, containing 636 acres of exceedingly good land in high cultivation. It has an elegant mansion house in complete repair when left and very well furnished. Every convenient out house and office, with stables and coach house, cow house, dove house. A large garden containing the best collection of fruit trees and plants of any in the province. Also 7 very neat and commodious tenements upon the premises.” So that is the last documentary reference from the 18th century that I have discovered, and, as you see, it does not mention the slave quarters specifically.

However, in 1814, one of the next owners whose family held the property from 1810 until the 1860s. In 1814 he listed his property and this is taken from some research that was done by Radcliffe Seminar students back in the 1970s. One of them wrote down on a note card and kindly shared with me a listing of the property of Jacob Tidd which was signed by him in 1814. She does not remember where it came from. I was not able to discover it in any of the various places that I did research, so I am offering a reward for the source of this document, because, as you see, it mentions the slave quarters for the first time. It lists the land, lots of ground with their improvements and dwelling house built in 1725 owned by Jacob Tidd on February 1st, 1814, being in the tenth district of Massachusetts in the town of Medford. One dwelling house situated on the west side of the old road from Boston to Medford village three stories high, built of brick and wood about 45 feet by 25 feet, an out house (and then it says in parentheses) slave quarters, partly brick and partly used for a wash house, etc. Because, of course by then, there were no more slaves in Massachusetts, slavery having been outlawed here in 1781, two barns, 18 acres of land, about said house, being all the westerly side of the road, and various other property. It is signed by Jacob Tidd, and the value of his holdings was $16,140 (by then we were dealing in dollars). There are several inventories relating to Jacob Tidd’s probate documents which are in the Massachusetts Archives and what is particularly interesting is that they refer to all of the rooms that you would expect in the main house except the kitchen, but they both (the one for the dower’s, the widow’s rights and inventory of the estate) list a keeping room in the main house, but they also list a kitchen chamber, so my supposition is that this out kitchen was still being used as the main kitchen at that time.

Now we are skipping to 1874 and the trail gets hotter, I think. Samuel Adams Drake wrote Historic Fields and Mansions of Middlesex. He devotes a large section to the Royall house. This is the earliest photograph that I know about of the building. It is a stereopticon view and, therefore, is likely from the 1870s also. This is the slave quarters, and as you can see, then the brick portion was whitewashed. But Samuel Drake, who did a lot of research and may even have looked at original documents in addition to reading Charles Brooks’s history which came out in 1855. He said, “The brick quarters which the slaves occupied are situated on the south side of the mansion and front upon the courtyard, one side of which they enclose. These have remained unchanged and are, we believe, the last visible relics of slavery in New England.” So at that time, there may physical evidence in the house that they were slave quarters.

Other late 19th century views give you an idea of the building from various angles. They show that the upstairs of this building was used for storage in part. At least there is a great door to access the storage area above. They show that the doors that are here now were there before. There is another view that shows you that a little later there was another barn built directly opposite the garden front of the Royall House, but you see that the aspect of this building had not changed. Here it is from the other side. I don’t know what that little triangular piece is up on the gable, perhaps it is a pigeon roost, or something. And you can see there are other activities around the site at that time, grape arbors and various things.

Another view showing that same side and showing that the house is connected to this building by a one-story shed. This shows the fact that the windows on that side were also not the same as they are now. And then, a couple of very good quality photographs from the 1880s taken by Wilfred French, one of our famous early historic photographers. This shows that there was, at first, an addition, on the south side of the building, as well, and then later it was removed.

Now I’d like to take you through the physical evidence that I found in the building that this is indeed an 18th century building, and the reasons that I think that both parts of the 18th century. First of all, there are good 18th century roof frames. This is old part, the brick part; a detail in the old part where you can see port and beam timber framing held together with pegs and with mortises and tenons, just what you would expect in the 18th century. This is the part above us and it is perfectly easy to tell when you are up there that that chimney was added onto the chimney of the brick part. The timber framing in this room also is characteristic of the 18th century, although not the way it is painted and finished with plaster between the joists now, and I am sure that at that time, it wasn’t. The chimney arch in the basement of the old part is perfectly typical of the 1730s. And then on the exterior, perhaps you can see that the walls on this side, which was the fancy side facing the mansion are laid up in Flemish bond, that is the headers and stretchers alternate in different rows in order to give a sort of diamond pattern to the brickwork, which was very fancy in those days. Our Otis House, in fact, is Flemish bond on all sides except the rear of the ell.

Now I want to tell you a little bit about the evolution of this building and this particular building site. And I should say that John Hooper who wrote an article about the slave quarters which he read to the Medford Historical Society in 1900 had it all figured out. Can you see this line in the brickwork, the kind of line that you wouldn’t normally see in a brick wall? His contention, with which I agree, is that there was first a building right here, a small building, maybe 11 feet by 20 feet, and in fact, the foot print of the cellar down below this part matches that of the original building. There is no cellar under that end of the building. It was a one-story structure. It had one brick end, and that brick end was incorporated into the new out kitchen, which I believe was built in the 1730s. Here is a detail where you can see that this is just not the kind of thing that you usually find in a brick wall. It is pretty obvious, I think. The building that existed here before the brick part was built was subsequently torn down and this quite lengthy wooden part was build, and I believe it was built sometime after maybe 1740, and certainly before 1777. I think it is shown quite clearly in the plans that Pelham made. They added onto the chimney in this part of the addition, and when they got to the chimney stack outside of the roof, they built up together the two chimneys. The left hand part is the old part and the right hand part is the added chimney, and then they topped it off with brickwork combining the two sets of flues, which I think is pretty clear still, as well.

The Royall House Association, another confirming bit of evidence, was established in 1905, and as the by-laws say, for the purpose of acquiring the colonial residence of Col. Isaac Royall with the slave quarters, so it was pretty well in people’s minds by that point that these were the slave quarters. The Royall House Association undertook remodeling and one thing that they did was to redo the fireplace in that room. It had probably already been subject to remodeling for various reasons of efficiency or changing use, but what they did to it is to make it look older when they restored it, and so that great chimney lintel is not from the 1730s, it is from the early 20th century. The problem is that we can’t any longer read the evidence that was here before the restoration and they didn’t as far as I know leave written records to tell us (I think I would also offer a reward for those), nor do we know who did the work, although Charles Dunham is mentioned as an architect who worked on the restoration in 1917. We know that Joseph Chandler was involved in the restoration of the house, but I frankly think that he might have been more authentic than this work here.

That would have been there, back there, which you will be able to examine when the lights come on. But to my mind the most compelling evidence that this building was, in fact slave quarters was the doors on the courtyard side. With door steps and framing made specifically to accommodate these doors. There they are the doors on this side of the building, just to remind you. In this room, you see how the vertical darkened studs are not evenly spaced? There is a wide spacing so that there was intended to be a door there originally, also in the next bay. I am not so sure about the door in the far end, because that door does not seem to fit the original studs, but it may have been made to accommodate the shed that connected the building with the house in the beginning. But for the other, I just think that they were intended originally to be that way, and at first I balked at the idea that there was a fireplace in this room, but the other two rooms in this space were not heated. But I now believe that this was the case, that some of the slaves slept in unheated rooms. And I really can think of no other reason in a farm building to have so many doors.

Just a word about the south, you may have seen illustrations like this one that show rows of one story slave quarters. These are common even today in the South. But according to Ed Chappell, who is the director or architectural research at Colonial Williamsburg, these individual units are characteristic of the 19th century. In the 18th century, slaves were often housed in buildings that accommodated other uses as well, like this one, and he said that you find this kind of an arrangement often in Charleston, South Carolina. Here, for example, is a combination slave quarters and summer kitchen at Arlington House in Arlington County, Virginia, built in 1818, and here is the plan, on which one side says quarters and the other side says summer kitchen.

My conclusions based on all the evidence that I have examined is that this building was used as slave quarters. The reasons, as follows, to reiterate:

- There were too many slaves who lived here to be accommodated in the house or in other named buildings on the property.

- Because of the probable use of the term slave quarters in the 1814 document. It is in parentheses, so that there is a possibility that the researcher could have added it herself, but it seems unlikely.

- By the fact that Samuel Adams Drake, a thorough historian, found them to be such in 1874 when, as he says, they had remained unchanged.

- And then the notations on the HABS drawings which must have been based on evidence that people gave them that this was, in fact, divided into three rooms, I think is confirming evidence.”

About the author: One of the first graduates of Boston University’s Preservation Studies program, Anne Grady has authored historic resource surveys, National Register and National Historic Landmark nominations, and in-depth historic structures reports for many of the state’s most prominent buildings. In total, she has studied and advised on the preservation of more than 100 buildings, among them such well-known landmarks such as Boston’s Old South Meeting House, the Hancock-Clarke House in Lexington, the Gropius House in Lincoln, and the Spencer-Peirce-Little House in Newbury.