by Margot Minardi

In recent years the Royall House and Slave Quarters has adjusted the museum’s mission to focus squarely on the enslaved Africans who lived and worked at the Royall family estate. No figure has been more significant in the reinterpretation of the site’s significance than the woman now known as Belinda Sutton. In a petition to the Massachusetts legislature in February 1783, she is identified only as “Belinda an Affrican.” In stirring language, the petition narrates Belinda’s idyllic childhood in Africa, her trauma and terror at being taken captive and shipped to America as a young girl, and her utter despair at learning that “her doom was Slavery, from which death alone was to emancipate her.” Writing at the tail end of the Revolutionary War, Belinda (or her amanuensis) lamented bitterly that “Fifty years her faithful hands have been compelled to ignoble servitude for the benefit of an Isaac Royall, until…the world convulsed for the preservation of the freedom which the Almighty Father intended for all the human Race.” With the start of the war, her master, a Loyalist, fled, first to Nova Scotia and then to England. Finally, Belinda requested a pension out of Isaac Royall’s property, an estate which, as the petition pointed out, was partly a product of her own uncompensated labor. The legislature granted Belinda’s request, though it is not clear that the pension was consistently paid to her after that.

As Belinda’s petition observed, it was fundamentally unfair that enslavement deprived her not only of basic human dignity but also of the ability to acquire property and dispose of her own time: “What did it avail her, that the walls of her Lord were hung with Splendor…the Laws had rendered her incapable of receiving property—and though she was a free moral agent, accountable for her actions, yet she never had a moment at her own disposal!” Drawing on the logic of these lines, some commentators have called Belinda’s demand a call for reparations for slavery. That Belinda was seeking restitution for her uncompensated labor and unconscionable suffering is undeniable. But is “reparations” an accurate description for what she actually got?

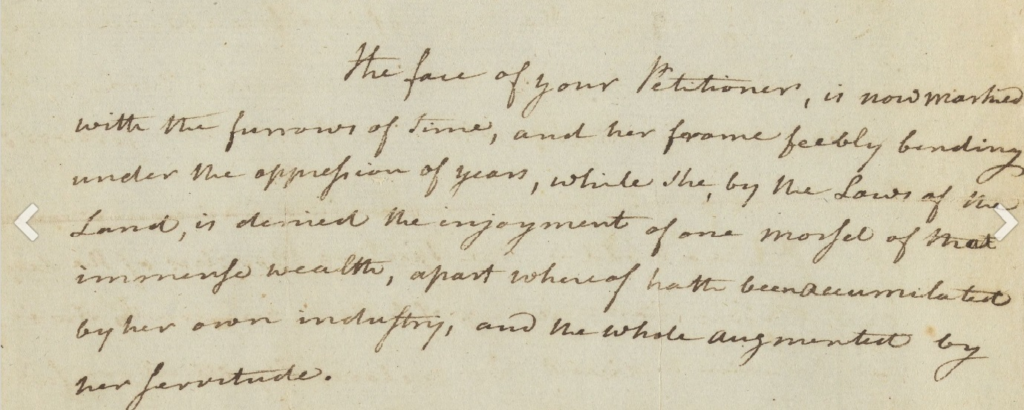

While it is tempting to read the fact that the legislature granted Belinda’s request as evidence that the petition’s argument in favor of reparations for slavery succeeded, such an interpretation drastically mischaracterizes what made the petition effective in its particular context. Belinda may well have been asking for reparations for slavery, but that’s not necessarily what the legislators gave her. However compelling the language of the petition, there is a very good chance that the powerful rhetoric was entirely incidental to the petition’s success. Within the received framework of slavery and dependence in eighteenth-century Massachusetts, the legislators could grant her request without making any concession whatsoever to the petition’s radical implications. To understand this aspect of the petition, we have to look beyond the equal rights rhetoric that presents Belinda as a kind of Revolutionary radical: a “free moral agent” claiming what is rightfully hers. The petition gives us another Belinda as well. This one is aging and ill. In the words of the petition, she is “marked with the furrows of time…her frame feebly bending under the oppression of years.” This language positions Belinda as an object of pity, rather than a claimant of rights.

To understand the significance of presenting Belinda as a pitiable old woman, we have to consider the ambiguous state of slaves of absentee Loyalists in Revolutionary Massachusetts. There was a simple procedural reason for legislators to approve Belinda’s request without necessarily accepting the principled antislavery and egalitarian argument articulated in her petition. After Isaac Royall fled Medford in April 1775, the Revolutionary government of Massachusetts confiscated his estate, as it did those of other Loyalists who left during the war. In August 1775, the Massachusetts government investigated what was happening on these estates. The investigators found that “many of them who are left in possession under pretence of occupants are only negroes or servants.” In other words, Loyalists left for Canada or England, and depending on how you look at it, they either abandoned their homes with servants and enslaved people still living there, or they entrusted their estates to the servants’ and slaves’ care. What is evident from the available documentation is that some of these bound laborers made the best of being left behind. For instance, after his loyalist master fled, Tony Vassall, an enslaved man in Cambridge, took up residence on his master’s brother’s land, did some farming for himself, and hired himself out to work on other estates. But not everyone was so equipped to support themselves. For those slaves of Loyalist absentees who were too old or too sick to care for themselves, the Massachusetts government determined that they might be permitted monetary support out of their masters’ confiscated property. At one level, Belinda’s petition was an eloquent request that this policy be enforced.

Understanding the reasoning behind this policy requires taking a step back in time. Traditionally, local and provincial governments declined to involve themselves in the material support of aging slaves or ex-slaves. A Massachusetts law dating to 1703 made it illegal for a master to free a slave without providing a bond to keep the freedperson from becoming a financial burden to his or her town. Providing for all members of their households, including servants and slaves, was a basic obligation of heads of household. By an extension of this logic, lawmakers determined that Belinda, who had once been enslaved by Isaac Royall, ought to be supported out of his estate. So, although Belinda’s petition made a forceful case against slavery in natural rights terms, her request could be granted within the institutional logic of slavery. By putting Belinda’s petition in the context of the government’s efforts to figure out what to do with Loyalist property, we can see those parts of the petition that present her as a suffering old woman as absolutely crucial to Belinda’s claim. They demonstrated that Isaac Royall had not fulfilled his obligation to see that his former slave was sufficiently provided for, so the state stepped in and used his confiscated property to get the job done for him. The fact that the money used to compensate Belinda was to come out of Royall’s estate, and not directly from state coffers, undoubtedly made the legislators all the more amenable to approving her petition.

Interpreting the petition in this light shows an enormous gap between how Belinda (or whoever helped her write her petition) thought about freedom and independence and how the legislators conceived of these same ideas. Belinda presented herself as a “free moral agent,” whose autonomy and independence had been unfairly compromised by Isaac Royall’s greed. The legislators saw her not as an independent agent but as a profoundly dependent person: someone who relied on either her master or the state to ensure her own well-being. Their ideas of economic independence and free moral agency simply did not extend to an aging woman of color.

We don’t have any record of the reasoning behind the legislators’ decision to grant her the petition. It is quite feasible that they felt genuine sympathy for Belinda. But it’s difficult to conclude that they wholeheartedly accepted her reparationist reasoning because the legislators ignored other petitions from people of color making similar antislavery arguments, although asking for very different forms of redress. To give just one example, in 1780, a group of black men petitioned the state for assistance. These men argued that “by Reason of Long Bondag and hard Slavery we have been deprived of Enjoying the Profits of our Labour or the Advantage of inheriting Estates from our Parents as our Neighbours the white peopel do.” Like Belinda these men were free, and they pointed out the hollowness of freedom without fair compensation for the labor they had performed under slavery. But these men could not lay claim to the estate of a Loyalist absentee. They asked instead not to be burdened with taxes. The legislators did nothing for them.

Belinda Sutton’s 1783 petition is striking to modern readers for the searing moral clarity of its rhetoric—and for the fact that Belinda actually succeeded in making her case. In its original context, though, the power of the rhetoric might not have had much to do with Belinda’s ability to extract the promise of a pension from the legislators. The genius of Belinda’s petition is that it simultaneously made a savvy case drawing on the prevailing laws and practices of her eighteenth-century world and spoke truth to the power that ruled it.

Sources: in addition to the sources linked in this essay, this essay quotes from the Massachusetts Archives Collection, Volume 231: Revolution Resolves, 1781, p. 115 (re abandoned Loyalist estates) and from the 1780 petition of Paul Cuffee and other residents of Dartmouth, Mass., reprinted in Herbert Aptheker, A Documentary History of the Negro People of the United States (1967), pp. 14-16.

Margot Minardi is an Associate Professor of History and Humanities at Reed College in Oregon, where she teaches courses in colonial and Revolutionary American history, early African American history, and social reform. She is the author of Making Slavery History: Abolitionism and the Politics of Memory in Massachusetts, published in 2010, and is a member of the Royall House and Slave Quarters’ Academic Advisory Council.